Postcard from a Fellow: Ernie Osburn’s year of two summers

July 23, 2020

Hello everyone! I hope this postcard finds you healthy and safe. If you don’t know me already, I’m Ernie, an IGC fellow from the Biological Sciences department. My research focuses on how landscape history influences soil microbial communities and their ecosystem functions. My goal today is to entertain you with stories about my summer research adventures. Only one problem – this summer has been a weird one. Not sure if you guys have heard, but there is a global pandemic going on right now that has messed up everyone’s summer plans, including my own. As a result, I find myself most days in an empty lab in a mostly empty building doing tedious, mind-numbing lab work. Nothing too exciting to write about, unfortunately . . . However, I was fortunate enough this year to experience two summers: the current northern hemisphere summer as well as the austral (southern hemisphere) summer while doing field work in Antarctica during January and February. Antarctica is much more interesting than Derring Hall, so I’ll write about my time “on the ice.”

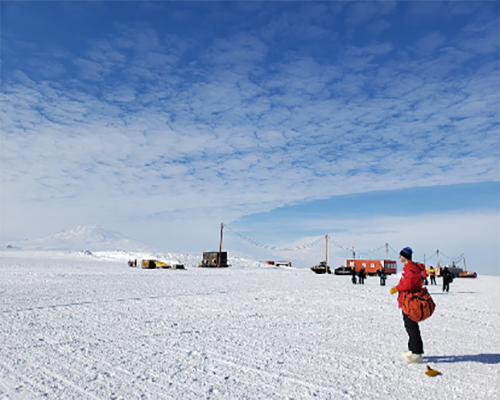

My lab mate Sarah and I began our Antarctic adventure on December 12th 2019. Our travels began with about 24 consecutive hours of airline flights from Roanoke, VA to Washington D.C. to Houston, TX, to Auckland, New Zealand, and finally to Christchurch, New Zealand. Because of time zone changes, we lost a day in transit and landed on December 14th. The next day, I attended some training sessions and was issued my extreme cold weather gear (ECW) at the U.S. Antarctic Program facility in Christchurch, NZ. Normally, the flight down to “the ice” is scheduled for the following day, but because of weather delays, we did not fly out until December 17th. The flight was a loud, uncomfortable, 8 hour trip in jump seats on a C-130 with my legs interlocked with those of the people across from me. After the plane landed on the Ross Ice Shelf, we were transported to McMurdo Station.

While in Antarctica, about half of my time was spent living at McMurdo station and processing samples in the lab facility there. McMurdo station is located on Ross Island just off the coast of the Antarctic continent and is the central base of operations for the U.S. Antarctic Program. McMurdo is the most populated place in Antarctica and is essentially a functioning town, complete with a fire department, a water treatment facility, a waste management facility, a library, a hair salon, a general store, and three bars. At its busiest, there were more than 1,200 residents at McMurdo, a mixture of researchers, support staff, and military personnel. Everyone on station eats meals in “the galley,” a big cafeteria. The food is generally all frozen and non-perishable, with fresh food available very rarely. So not the best. People live in very close quarters at McMurdo – everyone is assigned a dorm room with 1-3 roommates and bathrooms are all communal. Also, social life at McMurdo is surprisingly lively. Nearly every night of the week there are events, often involving live music. Most notably is the annual New Year’s Eve concert/party called ‘Ice Stock.’ One interesting quirk of McMurdo is that people like to dress up in silly costumes for these events. There are lots of costume options readily available on station (for reasons unknown to me), so I decided to participate a couple of times after coming across some fun animal costumes. In general, if you thought living in Antarctica would be an isolating experience, you would be very wrong! If you’re interested in learning more about life at McMurdo station, check out the ‘Antarctica: A Year on Ice’ documentary, which is free with Amazon Prime.

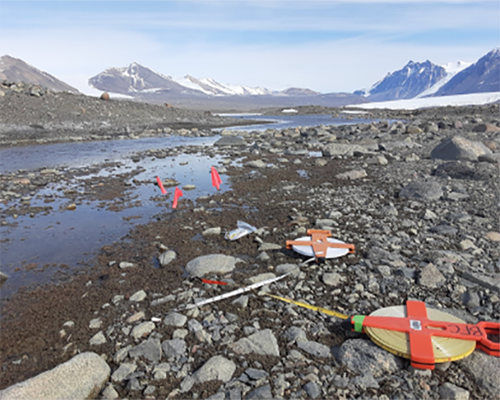

The other half of my time in Antarctica was spent living at field camps in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. The Dry Valleys are the largest ice-free areas in Antarctica. For about two months of every year during the austral summer, temperatures get high enough that ice melts, forming streams. These streams flow from glaciers up in the mountains to freshwater lakes at the bottom of each basin. Most of the lake surfaces are covered by a layer of permanent ice, though liquid water ‘moats’ form around the edges of the lakes in the summer months. Most of the lake basins are ‘endorheic,’ meaning they do not have an outflow to the ocean. This causes minerals to accumulate over time, which causes the lakes to form saline layers.

The Dry Valleys are located on the Antarctic continent across McMurdo Sound and are only accessible by helicopter. My first trip out to the Dry Valleys was my first time flying in a helicopter and it’s a thrilling experience! While living at the field camps, I slept in a tent each night, which is very difficult with 24 hours of daylight. In fact, I did not see the sun set during my entire two month stay in Antarctica! The field camps also have permanent structures, including small lab spaces and a heated living space with a gas or solar powered appliances such as stoves, ovens, refrigerators, and freezers. The field camps even have wi-fi! The only amenity missing from the field camps is running water, but otherwise living in the camps is surprisingly comfortable. While in the Dry Valleys, Sarah and I hiked to various locations in multiple lake basins to sample soils and microbial mats. These microbial mats are the “forests” of the Dry Valleys and are the most conspicuous life found there. The mats form in lakes, streams, and wet soils, and there are green, red, orange, and black mat varieties, each composed of different microbial taxa. Our goal with these samples is to understand how differences in soil nutrient availability due to the unique geologic histories of the different lake basins has influenced the structure and ecosystem functioning of microbial communities present in these environments.

By mid-February, the Antarctic winter was well on its way and it was time for our field season to end. Sarah and I flew back to Christchurch on a US Air Force C-17 and we were then lucky enough to spend a couple of week travelling around New Zealand before coming back to the U.S. As you might imagine, New Zealand is a very different environment from Antarctica and maybe even more stunningly beautiful. It was interesting adjusting back to a more normal society and being surprised at seeing normally mundane things that were not present in Antarctica, such as trees, dogs, children, and the night sky. Then, nearly immediately after arriving back in the U.S., the COVID crisis began and I was stuck in my apartment for a few months working on data analysis and writing.

Now that my 2nd summer is here and our lab has re-opened, I spend most days doing lab processing and analysis of the soil samples we collected in Antarctica and from other projects. My lab work consists of various chemical analyses of soils as well as DNA-based analyses of soil microbial communities. These DNA analyses involve isolation of DNA from the samples and lots of PCR (check out my growing collection of PCR plates below!). The lab work isn’t particularly exciting, but at least it is going smoothly thus far. Anyways, this might be the longest post card in history, so I’m going to stop it here (I’m impressed if you actually read this far!). I hope everyone is doing well during these challenging times and I hope to see everyone soon.