VT researcher working to provide clean water to Appalachia

June 20, 2020

FROM CALS VT NEWS | JUNE 20, 2020

More than 2 million Americans live without access to safe drinking water or adequate sewer sanitation, according to a 2019 study by the U.S. Water Alliance. That includes around a quarter-million people in Puerto Rico and half a million homeless people in the United States. The biggest chunk, though — around 1.4 million people — are United States residents who live in homes that don’t have proper plumbing or tap water.

They are clustered in five areas: California’s Central Valley; predominantly Native American communities near the four corners of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico; the Texas-Mexico border; the Mississippi Delta region in Mississippi and Alabama; and central Appalachia. Virginia alone has around 20,000 homes without plumbing.

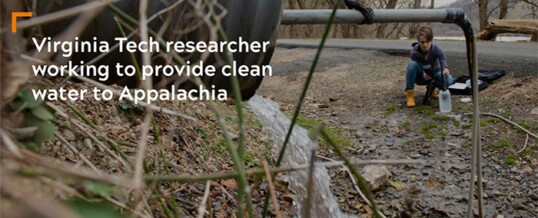

Leigh-Anne Krometis, an associate professor of biological systems engineering which is in both the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and College of Engineering at Virginia Tech, is one of the foremost experts on water quality and availability in Appalachia. And while the basics of her work seem, well, basic — “I just spent a decade proving that not having sewers is a bad thing, which we’ve known for literally thousands of years,” she said — the implications are more complex.

Often, the best minds in American civil and environmental engineering are looking abroad, at how to bring clean water to remote villages and slums in developing countries. The crisis over lead in the tap water in Flint, Michigan, was a reminder that all over the United States, people lack access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation.

In the past three years, Krometis has authored a series of studies of water quality and availability in the Appalachian region. In 2017, she published “Tracking the Downstream Impacts of Inadequate Sanitation in Central Appalachia” in the “Journal of Water and Health.”

That article looked at what happens to streams when homes near them don’t have proper plumbing. Usually, that means a “straight pipe” that carries untreated sewage into an unlined hole in the ground, which drains either directly or indirectly into a stream. Krometis and her team found E. coli bacteria consistent with untreated human waste in those streams, in spots that were correlated with their proximity to homes without proper sewage systems. Sometimes the contamination carried as far as six miles downstream.

Krometis’ newest article on the subject, “Water Scavenging from Roadside Springs in Appalachia,” published in May 2019 in the “Journal of Contemporary Water Research and Education,” connects her earlier research on wastewater to the issue of drinking water. Some untold number of people in Appalachia drink untreated water from springs or streams — often the same streams that are close to straight sewage pipes. Krometis and her team tested the water at 21 springs used for drinking water, and more than 80 percent of them tested positive for E. coli.

Krometis also surveyed people who drink untreated spring water, and found that most of them do have running water in their homes, often from wells. They said they preferred the spring water because it tastes better than their tap water, or because they don’t trust the quality and reliability of the water in their homes.

Fixing these two interrelated problems, of wastewater and drinking water, isn’t easy. The homes that use straight pipes and roadsides springs tend to be far away from the nearest municipal sewer and water systems, and often separated by mountains and ravines. It could cost $50,000 or more to hook one of these homes up to a sewer system, even if there is one nearby, Krometis said. Septic tanks are usually unsuitable because the soil isn’t deep enough.

“These are legitimately challenging engineering problems, and they require a lot of money, and these places don’t have a lot of money,” she said. “We haven’t figured out ways to get water and sewer to extremely rural areas, and there are also huge issues with the homeless and the working poor in urban areas.”

There are cheaper and easier solutions, of the type used in developing countries. Public water kiosks for drinking water are one, and are already in use in some parts of Kentucky and West Virginia; small water or sewer treatment devices installed for each home or cluster of homes are another option. Krometis supports these tactics, though she sees the political and cultural obstacles to using them in the United States.

“The technologies that are best practices in Africa or Southeast Asia, we don’t use in the United States. They’re unacceptable because we’re a developed country,” she said. “But in my mind, if you have somebody who’s impoverished and doesn’t have access to clean water, that’s a problem that we need to address.”

People are hesitant to give residents of Appalachian mountain hollows or California’s dry and dusty farm town water and sewer systems that aren’t up to the standards of their fellow Americans in cities and suburbs. Krometis understands that hesitation, but she also understands that many of those poor Americans are going without any access to reliable, clean water.

“I see both sides of the coin,” she said. “The problem is, we’re not even having that debate.”

Written by Tony Biasotti